Teaching Sustainability

In a globalizing world of limited resources and unlimited ingenuity, colleges and universities play a vital role in preparing students to meet the sustainability challenges of the future. The imperatives of sustainability point not only to new course content, but also to new ways of teaching that content. As a project with relevance across the disciplines, sustainability presents a valuable paradigm for rethinking pedagogy.

In a globalizing world of limited resources and unlimited ingenuity, colleges and universities play a vital role in preparing students to meet the sustainability challenges of the future. The imperatives of sustainability point not only to new course content, but also to new ways of teaching that content. As a project with relevance across the disciplines, sustainability presents a valuable paradigm for rethinking pedagogy.

What is Sustainability?

What is sustainability? What do we want to sustain? An important part of teaching sustainability issues involves keeping these questions always open and alive. Sustainability offers a novel framework for asking enduring philosophical questions: What is the good life? How do we create a better world? Thinking and teaching about sustainability are future-oriented projects, but the relevance of sustainability principles and practices must be articulated in the present.

The term “sustainability” has an important history in development literature. In 1983, the United Nations convened the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), known informally by the name of its chair, Gro Harlem Brundtland. The Brundtland Comission’s report, Our Common Future (1987), contains one of the most often cited definitions of sustainability:

“Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It contains within it two key concepts:

• the concept of ‘needs’, in particular the essential needs of the world’s poor, to which overriding priority should be given; and

• the idea of limitations imposed by the state of technology and social organization on the environment’s ability to meet present and future needs.”

The scope of sustainability is frequently described as including three spheres – social, environmental, and economic. To use an accounting metaphor, sustainability projects must be evaluated according to a “triple bottom line” of social, environmental, and economic responsibility. A Venn diagram depicts the interdisciplinarity of sustainability as a field of inquiry:

Sustainability is at once an integrative discipline and a multidisciplinary project; it has statistical, scientific, and humanistic dimensions. With its focus on specific problems and particular solutions, sustainability suggests place-based and project-based approaches to student learning. Teaching towards sustainability also reminds us that pedagogy is a civic project; there are important ties between classroom and community.

Tips for Teaching Sustainability

Beth Conklin, Vanderbilt University Professor of Anthropology, offers various suggestions for using ecological footprint calculators well and for teaching about sustainability issues generally:

- Beware of Student Overload. The rhetoric of urgent and global environmental crises can overwhelm students when they consider the immensity of the problems humanity face and the difficulties involved in coping with them. These feelings of cognitive or emotional overload can cause students to feel disengaged, disempowered, and even resentful, which can disrupt the learning process.

- Avoid Doom and Gloom. While teaching students about the many challenges to environmental sustainability will necessarily introduce some risk of overload, teachers can limit this by being sure to discuss environmental success stories. For example, this may include discussion of environmental policies or movements that have succeeded in mitigating pollution, conserving resources, or promoting ecological resiliency. Whatever the success, incorporating them into courses can help students envision a future that is shaped by their agency, and avoid any descent into cynical resignation or fearful reaction.

- Focus on Quality of Life Issues. Students facing the emotional overload of environmental problems can easily feel that their entire lifestyle is threatened by resource limits and the environmentalists who champion living simply. Educators can sometimes add to this sense of threat by taking a moralizing, prescriptive, and unyielding approach to more sustainable lifestyles. An alternative approach is to engage students by discussing their definitions of happiness and a quality of life, and whether they are correlated with high levels of consumption and resource use. If students reflect prior research findings (Consumerism and its Discontents, To Do or to Have? That Is the Question), they will often argue that the two are not highly correlated, providing a basis for a positive discussion of alternative lifestyles and social changes associated with them.

- Peer Engagement and Support. Engaging students in group discussions and projects in which they have the opportunity to dialogue and support one another can help to alleviate these feelings of overload. It also can allow for the moments of problem-solving, debate, analysis, teamwork, and reflection that are so crucial to developing the critical thinking and leadership skills students need to face complex problems.

- Student Analysis of Data. Students may learn more about a given environmental problem by wrestling with empirical data for themselves, rather than receiving pre-digested analyses from lectures or secondary sources. In doing so, they will not only grapple with methodological and theoretical issues of data analysis and presentation, but they will be empowered to examine environmental issues with greater nuance and insight.

- Deconstruct Eco-rhetoric. Spend time investigating the historical origins and often conflicting uses of environmental terminology such as “sustainability,” “environmentalism,” “stewardship,” “nature” itself, and other language. This will provide valuable teaching moments about the historical development of environmental studies, and it will empower students to examine environmental problems and solutions more critically.

- Precautionary Principle. Succinctly defined, the precautionary principle states that, if an action risks causing harm to the public or the environment, and there is no scientific consensus that it is indeed harmful, the burden of proof that it is NOT harmful falls on those taking the action. An often debated principle, it provides a useful starting point for class discussions of how to make decisions under conditions of uncertainty. It also offers an opportunity to discuss policy options regarding resource use and the tradeoffs between potential environmental harm on the one hand, and economic or political costs on the other.

- Embrace Interdisciplinarity. A critical and thorough understanding of issues related to environmental sustainability necessarily involves contributions from a wide variety of disciplines throughout the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities. This may be daunting for students and educators alike since it often requires us to think outside of our intellectual expertise. Doing interdisciplinarity well can be a challenge, but it becomes easier with a more effective use of resources on one’s campus community and beyond, such as team teaching with a colleague from a different discipline, organizing guest lecturers from across campus, or bringing in guest speakers from the local community. Mostly, however, it requires a courage to step out of one’s comfort zone and explore topics that will enrich the learning experience for our students and that will stimulate us to think in new ways as educators.

Interdisciplinary

Teaching sustainability is both exciting and challenging because of the interdisciplinary nature of the problems at stake. When teaching these issues, instructors are often working outside their own areas of expertise. How do you bring new content knowledge into the classroom without overburdening yourself? Ways to build interdisciplinary classrooms include:

Guest Speakers:

- Guest speakers extend the boundaries of the classroom, helping students to see the course as a part of a larger network of ideas and conversations.

- The expert’s visit presents an external motivation for students to engage with readings and assignments.

- Careful planning can help to ensure that guest contributions will enhance student learning.

- Let guests know ahead of time the topic of the course and how their visits fit with the themes of the class.

- Assign students to submit questions in the expert’s area of interest.

- Avoid presentations; invite the expert to class to participate in an interview instead.

- Consider inviting guests with opposing views.

(Information on guest speakers adapted from David Cook’s comments in Teaching and Learning Exchange 12/2 (Winter 2005): 9, published by the University Teaching Services at the University of Alberta, Canada)Cooperative Learning:

Place-Based and Project-Based Learning

Teaching towards sustainability lends itself to place-based and project-based approaches to pedagogy. Although sustainability is a global goal, its problems and solutions are always importantly situated in local ecologies and communities. Instructors might consider taking a “bioregional” approach to teaching about place, encouraging students to think about their local watershed as a meaningful way to conceptualize community. In addition, focusing on sustainability solutions requires the cultivation of an imaginative experimentalism – the difficulties involved in transitioning to a more sustainable world can only be worked out in the process of formulating practical alternatives to the problems at hand.

Field Trips

Field trips bring people together in ways that go beyond traditional classroom experiences. Planning the logistical details of a field trip take time and foresight, but the rewards of a well-planned field experience can make it worth the effort.

- Be sensitive to time and place; it is impossible to plan for every contingency, but keep in mind the variability of seasonal weather.

- Don’t plan every minute of the trip. Create time for observation and “poking around.”

- Create solo time – consider having students bring a journal; offer the option of a reflective writing assignment.

Campus as Sustainability Classroom

Encourage students to think of the campus as a sustainability laboratory. Assign projects that allow students to create solutions to sustainability issues they identify in their own dormitories and dining halls. Get in touch with your campus sustainability coordinator to brainstorm projects and to help connect students with existing campus resources and organizations.

Classroom and Community

There is an important relationship between the university and the larger community of which it is a part. Teaching about sustainability is, in large part, a civic education. Instructors can encourage students to see not only their campus, but also the city and countryside in which it is located, as a sustainability classroom. Assign projects that help students to map and engage with sustainability issues and initiatives in the community. Consider assigning students to attend a city council meeting and write a response.

The CFT has a teaching guide on service learning for instructors considering incorporating action research and community engagement into their courses.

Teaching with Ecological Footprints

Using ecological footprints calculators is one valuable starting point for educators wishing to engage students in important dialogues about wide ranging issues of environmental sustainability and resiliency. Ecological footprints are calculations of natural resource use that assess environmental impacts. Typically they measure levels of resource consumption relative to resource availability, and they may be scaled to address the consumption of individuals, campus communities, cities, or entire nations.

There are two general types of calculators, “Ecological Footprint” calculators that attend to resource use across many resource categories, and those that are more specific to individual resources, most notably “Carbon Calculators.” Ecological footprint calculators are more complex since they address a broader diversity of natural resources and their uses, and they typically measure resource use against the total amount of resources available, thus accounting for some approximation of the natural limits to consumption. Carbon Calculators are measures of carbon resource consumption and are particularly useful as they pertain to one of the most significant environmental threats and policy issues of our time, namely climate change. They arguably are also good proxies for resource use generally since fossil fuel use is deeply embedded in all forms of consumption. Usually carbon calculations do not involve a measure of the total natural stock of carbon-based fuels or other resources, although their results may be analyzed in the context of levels of atmospheric pollution thought necessary to curb such problems as climate change.

Footprint Calculators

There are many varieties of ecological footprint calculators.

- Among the most reliable are those associated with the Global Footprint Network, the largest and most respected assemblage of expertise on ecological accounting. Collectively, the GFN has developed the largest and most complex datasets, and have set the standards by which roughly ninety percent of ecological footprints are calculated.

- Carbon Calculators. Some useful individual or household calculators are:

- For a comparative study of these Carbon Calculators conducted by Vanderbilt University’s own J. Paul Padgett, John H. Clarke, and Michael Vandenbergh, along with University of Washington’s Anne Steineman, please consult “A Comparison of Carbon Calculators.” 2008. Environmental Impact Assessment Review. 28: 106-115.

Classroom Uses of Footprints

The teaching moments afforded by footprint calculators are many and may be found in courses across the disciplines:

- Making the invisible visible. Much of our consumption and its many environmental impacts are not immediately obvious since they are obscured by our limited knowledge of any number of complex extraction and production processes. Ecological footprints encourage investigation and discussion of these processes and thus afford many opportunities to consider more fully human impacts on the natural world.

- Ecological literacy. Footprint calculations can give us a window into the ecological processes on which our ways of life depend, and thus provide occasions to discuss natural resource and waste management, particularly resource depletion, renewal, and toxification. Indeed, one benefit of footprint calculations is that they account for natural limits to resource use and therefore help students to attend to the overconsumption of natural resources, or “overshoot,” and its implications for future generations.

- Social literacy. Examining any ecological footprint will inevitably lead to investigations of the development of social systems – political, economic, and cultural – that shape human consumption and production. This will give students chances to achieve greater social literacy by learning such things as population demographics, consumption trends, economic development models, and policy priorities, just to name a few.

- Lifestyle choices. Ecological footprint calculators provide a unique feedback mechanism to students about the impacts of their consumption and the lifestyle associated with it. These highly personal choices – from diet to energy use – can be emotionally loaded and thus difficult to discuss. But when done tactfully, discussion of personal consumption can yield profound learning moments and new intellectual inquiry for the future. Among the most interesting questions is to what extent individual or household consumption can help solve problems such as climate change, something Vanderbilt researchers, Amanda Carrico, Mike Vandenbergh, and Jonathan Gilligan have researched with Paul Stern, Gerald Gardner and Thomas Dietz. Read their paper “Energy and Climate Change: Key Lessons for Implementing the Behavioral Wedge.”

- Environmental history. As footprint calculations are conducted over time, we may have more accurate assessments of cumulative impacts and thus have a clearer sense of how human society has shaped the natural world, and vice versa.

- Inequality. Footprint calculations compared over individuals, groups, or entire nations can provide a basis for wide-ranging discussions of inequality in resource use and waste, as well as the cultural, political, and economic systems that structure them.

- Policy analysis. More precise ecological accounting inevitably leads to discussions of different regimes of resource management, and thus offers opportunities to debate environmental policy at the local, national, or global level. Further, because ecological footprints can suggest multiple and highly different models of achieving sustainability, they may foster discussion about a wide range of environmental policies.

- Future directions. Ecological footprint discussions often lead to broad yet urgent student questions about how to define and construct a sustainable society. These are among the most difficult questions to answer because they are weighted with many complexities, uncertainties, and moral quandaries. Yet, such questions can provide openings for fruitful discussions of ways students may engage in new areas of research, policy, and leadership.

Limitations of Footprints

Footprint calculators are not without their limitations, however. Even so, the limitations of footprint calculators below afford their own teaching moments. In reference to Carbon Calculators, Mike Vandenbergh, Vanderbilt University Professor of Law, suggests several limitations are important to consider:

- Non-transparency. Carbon Calculators involve many data points and complex calculations. To make them accessible to a wide audience, they often simplify the results and fail to disclose some of the methods or data sources involved. This can limit the educational potential of the calculators. Therefore, it is important to understand the methods behind the calculations and make this part of the teaching process.

- Limited inputs. Some calculators are better than others. Some use too few or unreliable sources of data, while others do not. Therefore it is important to know the sources and methods of footprint calculations and to encourage students to think critically about them.

- Lack of context. Carbon footprint calculations can provide useful measures of carbon emissions, but their relevance is always dependent upon the teaching context. Thus it is important for educators to use them well and to contextualize their use within specific learning goals of the course and broader disciplinary orientations towards questions of sustainability.

- Skepticism. Many students may regard footprint calculations skeptically for a variety of reasons: the publicity and persuasiveness of climate change skepticism, the personal threat they may feel to their lifestyle, or the challenge they may feel to their political identity, just to name three. However, a critical, comprehensive, and not selective skepticism is something to be encouraged in students, and these reactions present teaching moments about the challenges of critical thinking and of the difficult choices posed by global environmental problems.

Ecological Footprints Resources

The Global Footprint Network supports the shift towards a sustainable economy by advancing the Ecological Footprint, a measurement and management tool that makes the reality of global limits central to decision-making. Ecological footprint projects can be an effective way to get students thinking about how sustainability intersects with their lives.

The latest results from Vanderbilt’s Green House Gas Emissions Survey may be especially useful for Vanderbilt faculty who wish to incorporate campus operations and sustainability into their courses. Some interesting highlights:

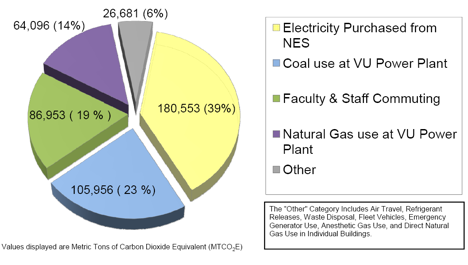

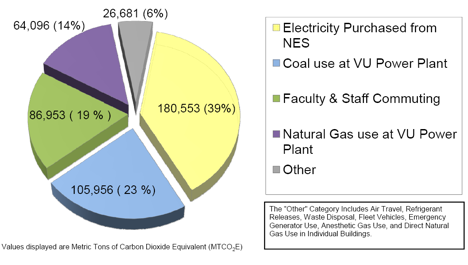

Vanderbilt University’s total carbon footprint for 2009 is approximately 464,240 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MTCO2E), a 2.4% decrease since 2005.

Of this total, 39% is electricity purchased from NES, 23% is from coal use at the VU power plant, 19% is from faculty and staff commuting, and 14% is from natural gas use at the VU power plant. This is represented in the pie chart below:

Carleton College’s Science Education Resource Center (SERC). A broad and multifaceted program, SERC is home to various resources and links that may be of use, including the Climate Literacy Network, the Pedagogy in Action website, and Teaching the Earth, among other valuable sites.

“The Ecological Footprint: Accounting for a Small Planet,” a film produced by Bullfrog Films in 2005, features Dr. Mathis Wackernagel and is a good introduction to natural resource accounting. Directed by Patsy Northcutt for the Global Footprint Network, it is 30 minutes long.

“Ecological Footprint Feedback: Motivating or Discouraging?,” an article by Amara Brook in Social Influence (Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 113-28, 2011), discusses the psychological challenges of motivating students with ecological footprints. While some students with high personal commitments to environmental sustainability were motivated to take action by their own footprint data, others without such commitments were not. This suggests at the very least that teaching with ecological footprints requires nuance and intentional discussion of their affective aspects.

Vanderbilt and Local Resources

Sustainability and Environmental Management Office: The SustainVU website offers an invaluable resource for instructors who want to familiarize themselves with the sustainability landscape at Vanderbilt. SEMO’s mission is to initiate, promote, coordinate, evaluate, and encourage environmental management and sustainability initiatives that improve Vanderbilt’s impact on the community and environment.

Vanderbilt Biodiesel Initiative: VBI is Vanderbilt’s student-run biodiesel production system, which converts waste vegetable oil into biodiesel fuel that is used by several VU diesel-fueled engines. One of the byproducts of this process, glycerin, is used to make EcoSuds soap, which is sold at several locations on campus. VBI aims to educate others about the viability of biodiesel as an alternative fuel.

Vanderbilt School for Science and Math: The School for Science and Math is a joint venture between VUMC and Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools offering high school students an interdisciplinary, research-centered learning experience. The School for Science and Math has developed innovative sustainability projects and learning experiences, including a biodiversity inventory of Vanderbilt’s campus, a bioassessment of the Little Harpeth River, and a videoconference with scientists in Hawaii to discuss the Pacific Gyre Garbage Patch.

Tennessee Higher Education Sustainability Association: THESA is a non-profit organization dedicated to supporting and promoting sustainability initiatives taking place within higher education institutions within Tennessee. It seeks to ensure that the societal movement toward sustainability is reflected in and promoted at college and university campuses across the state. The THESA website offers information about relevant conferences and other events, resources for instructors, information on model programs across the state, and updates on campus sustainability initiatives in the local news.

Organizations and Journals

The Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education: AASHE is an association of colleges and universities working to create a sustainable future. AASHE provides resources, professional development opportunities, and a network of support to enable institutions to model and advance sustainability in everything from governance and operations to education and research. Vanderbilt is a member of AASHE, with full access to their resources. Just be sure to use your @vanderbilt.edu address when signing up for an account.

The Association for Experiential Education: AEE is a nonprofit, professional membership association dedicated to experiential education and the students, educators and practitioners who utilize its philosophy. Their website includes information on relevant books, articles, conferences, and other resources.

The Journal of Sustainability Education: JSE serves as a forum for academics and practitioners to share, critique, and promote research, practices, and initiatives that foster the integration of economic, ecological, and socio-cultural dimensions of sustainability within formal and non-formal educational contexts. JSE is a peer-reviewed, open-access, trans- and interdisciplinary e-journal.

The Center for Ecoliteracy: The Center for Ecoliteracy promotes the green schooling movement. The Center is best known for its work with school gardens, school lunches, and integrating ecological principles and sustainability into school curricula. The Center for Ecoliteracy offers books; teaching guides; professional development seminars; a sustainability leadership academy; keynote presentations; and consulting services.

Going Green on Campus: This site, from Let’s Go Solar, has some useful tools for students to use to consider their campus consumption, resource use, and impact.

Books

Aber, John, Tom Kelly and Bruce Mallory, Eds. The Sustainable Learning Community: One University’s Journey to the Future. New Hampshire, 2009.

Barlett, Peggy, and Geoffery Chase. Sustainability on Campus: Stories and Strategies for Change. Boston: MIT Press, 2004. (available in the CFT library)

Blewitt, John and Cederic Cullingford, Eds. The Sustainability Curriculum: The Challenge for Higher Education. Earthscan, 2004.

Creighton, Sarah Hammond. Greening the Ivory Tower: Improving the Environmental Track Record of Universities, Colleges, and Other Institutions. MIT Press, 1998.

Hernandez, Carlos, and Rashmi Mayur. Pedagogy of the Earth: Education for a Sustainable Future. Kumarian Press, 1999.

Kahn, Richard. Critical Pedagogy, Ecoliteracy, and Planetary Crisis: the Ecopedagogy Movement. Peter Lang Publishing, 2010.

M’Gonigle, Michael and Justine Starke. Planet U: Sustaining the World, Reinventing the University. New Society Publishers, 2006.

Murray, Paul. The Sustainable Self: A Personal Approach to Sustainability Education. Earthscan, 2011.

Orr, David. Ecological Literacy: Education and the Transition to a Postmodern World. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992.

Rappaport, Ann and Sarah Hammond Creighton. Degrees that Matter: Climate Change and the University. MIT Press, 2007.

Stibbe, Arran. The Handbook of Sustainability Literacy: Skills for a Changing World. Green Books Press, 2010. (available in the CFT library)

In a globalizing world of limited resources and unlimited ingenuity, colleges and universities play a vital role in preparing students to meet the sustainability challenges of the future. The imperatives of sustainability point not only to new course content, but also to new ways of teaching that content. As a project with relevance across the disciplines, sustainability presents a valuable paradigm for rethinking pedagogy.

In a globalizing world of limited resources and unlimited ingenuity, colleges and universities play a vital role in preparing students to meet the sustainability challenges of the future. The imperatives of sustainability point not only to new course content, but also to new ways of teaching that content. As a project with relevance across the disciplines, sustainability presents a valuable paradigm for rethinking pedagogy.