A properly designed casting, a properly prepared mould and correctly malted metal should result in a defect free casting. However, if proper control is not exercised in the foundry-sometimes it is too expensive - a variety of defects may result in a casting.

These defects may be the result of:

(a) improper pattern design,

(b) improper mould and core construction,

(c) improper melting practice,

(d) improper pouring practice and

(e) Because of molding and core making materials.

(f) Improper gating system

(g) Improper metal composition

(h) Inadequate melting temp and rate of pouring

It creates a deficiency or imperfection.

Exceeding quality limits imposed by design and service casting defects are mainly 3 categories. These are:

(1) Major or most severe defects

(2) Intermediate defects

(3) Minor defects

Surface defects:

Due to design and quality of sand molds and general cause is poor ramming.Blow:

Blow is relatively large cavity produced by gases which displace molten metal form.Scar:

Due to improper permeability or venting.A scare is a shallow blow. It generally occurs on flat surf; whereas a blow occurs on a convex casting surface. A blister is a shallow blow like a scar with thin layer of metal covering it,Scab:

This defect occurs when a portion of the face of a mould lifts or breaks down and the recess thus made is filled by metal. When the metal is poured into the cavity, gas may be disengaged with such violence as to break up the sand which is then washed away and the resulting cavity filled with metal. The reasons can be: - to fine sand, low permeability of sand, high moisture content of sand and uneven moulds ramming.Drop:

Drop or crush in a mould is an irregularly shaped projection on the cope surface of a casting. This defect is caused by the break-away of a part of mould sand as a result of weak packing of the mould, low strength of the molding sand, malfunctioning of molding equipment, strong jolts and strikes at the flask when assembling the mould.The loose sand that falls into the cavity will also cause a dirty casting surface, either on the top or bottom surface of the casting, depending upon the relative densities of the sand and the liquid.

Penetration:

It is a strong crust of fused sand on the surface of a casting which results from insufficient refractoriness of molding materials, a large content of impurities, inadequate mould packing and poor quality of mould washes.

When the molten metal is poured into the mould cavity, at those places when the sand packing is inadequate, some metal will flow between the sand particles for a distance into the mould wall and get solidified. When the casting is removed, this lump of metal remains attached to the casting. Of course, it can be removed afterwards by chipping or grinding.

Buckle:

A buckle is a long, fairly shallow, broad, vee depression that occurs in the surface of flat castings. It extends in a fairly straight line across the entire flat surface.

It results due to the sand expansion caused by the heat of the metal, when the sand has insufficient hot deformation. It also results from poor casting design providing too large a flat surface in the mold cavity.

Buckling is prevented by mixing cereal or wood flour to sand.

Internal defects:

Blow holes:

Blow holes, gas holes or gas cavities are well rounded cavities having a clean and smooth surface. They appear either on the casting surface or in the body of a casting.

These defects occur when an excessive evolved gas is not able to flow through the mould. So, it collects into a bubble at the high points of a mould cavity ad prevents the liquid metal from filling that space.

This will result in open blows. Closed, cavities or gas holes are formed when the evolved gases or the dissolved gases in the molten metal are not able to leave the m ass of the molten metal as it solidifies and get trapped within the casting.

These defects are caused by :

i) excessive moisture content (in the case of green sand moulds) or organic content of the sand, moisture on chills, chaplets or metal inserts,

ii) inadequate gas permeability of the molding sand (due to fine grain size of sand, high clay content, hard ramming),

iii) poor venting of mould, insufficient drying of mould and cores, cores not properly vented, high gas content of the molten metal,

iv) low pouring temperature and incorrect feeding of the casting etc.

Pin holes:

Pin holes are small gas holes either at the surface or just below the surface. When these are present, they occur in large numbers and are fairly uniformly dispersed over the surface.

This defect occurs due to gas dissolved in the alloy and the alloy not properly degassed.

Visible defects:

Wash:

A cut or wash is a low; projection on the drag face of a casting that extends along the surface, decreasing in height as it extends from one side of the casting to the other end.

It usually occurs with bottom gating castings in which the molding sand has insufficient hot strength, and when too much metal is made to flow through one gate into the mold cavity,

Rat tail:

A rat tail is a long, shallow, angular depression in the surface of a flat rating and resembles a buckle, except that, it is not shaped like a broad vee.

The reasons for this defect are the same for buckle.

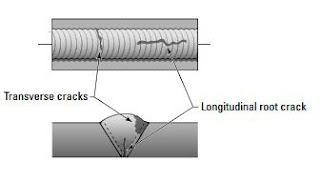

Hot tear:

Hot tears are hot cracks which appear in the form of irregular crevices with a dark oxidized fracture surface. They arise when the solidifying met does not have sufficient strength to resist tensile forces produced during solidification.

They are chiefly from an excessively high temperature of casting metal, increased metal contraction incorrect design of the gating system and casting on the whole (causing portions of the casting to be restrained from shrinking freely during cooling which in turn causes excessive high intern resistance stresses), poor deformability of the cores, and non-uniform cooling which gives rise t internal stresses. This defect can be avoided by improving the design of the casting and by having a mould of low hot strength and large hot deformation.

Shrinkage:

A shrinkage cavity is a depression or an internal void in a casting that results from the volume contraction that occurs during solidification.

Swell:

A swell is a slight, smooth bulge usually found on vertical faces of castings, resulting from liquid metal pressure. It may be due to low strength of mould because of too high a water content or when the mould is not rammed sufficiently.

Shift:

Mold shift refers to a defect caused by a sidewise displacement of the mold cope relative to the drag, the result of which is a step in the cast product at the parting line.

Core shift is similar to mold shift, but it is the core that is displaced, and (he dis-placement is usually vertical. Core shift and mold shift are caused by buoyancy of the molten metal

Misrun or cold sheet or short run:

This defect is incomplete cavity filling. The reasons can be: - inadequate metal supply, too- low mould or melt temperature, improperly designed gates, .or length to thickness ratio of the casting is too large. When molten metal is flowing from one side in a thin section, it may loose sufficient heat resulting in loss of its fluidity, such that the leading edge of the stream may freeze before it reaches the end of the cavity.